Playing in the Creative Sandbox

Time ago, I won by chance a one-month course on creativity from Melissa Dinwiddie, and I planned to write about this course and lessons about creativity for quite some time.

Time ago, I won by chance a one-month course on creativity from Melissa Dinwiddie, and I planned to write about this course and lessons about creativity for quite some time.

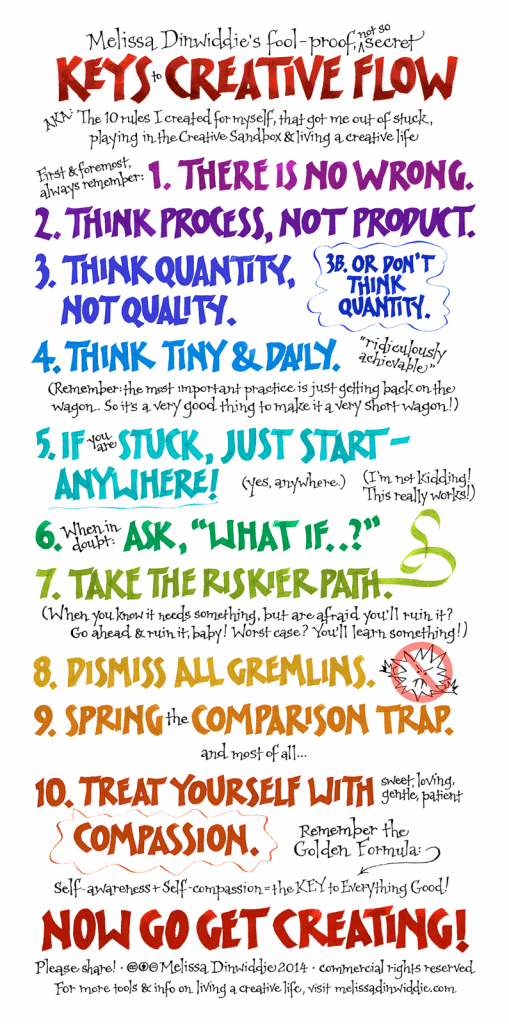

One of the most powerful elements in Dinwiddie’s course is her set of rules for the creative sandbox. Although she wrote this set of rules for artists that need to get their creative juices flowing again, these rules are applicable to research – which is a creative work – as well.

The creative sandbox is getting into the habit of making art for sheer fun for 15 minutes a day. Similarly, we could all benefit from a little random dabbling around in ideas that we otherwise would never pursue. The point here is not to spend your entire day playing in a research sandbox, but to escape to the sandbox every now and then, consciously, to explore ideas and see where the exercise takes you.

Let’s look at the 10 rules:

1. There is no “wrong.”

When you are fiddling with creative ideas that might or might not take you somewhere, you need to let go of prejudices you might hold against methods or previous research, and simply take a plunge and try out something. The goal of trying it out is not to find a solution to whatever problem you are studying, but to simply explore the possibilities of the method or approach you are trying out.

2. Think process, not product.

Creativity is a muscle you can train, creative thinking is a skill you can learn. And just like you would train for a tennis game by practicing a certain move over and over again, which is not something you actually do during a game, it is wise to focus on the process of toying around with ideas and trying out things when you start with research as a young graduate student.

3. Think quantity, not quality.

Again, here we are talking about playing around with creative research ideas – when it comes to publications, we want quality of quantity of course! When we are trying to develop that creative muscle, trying out a set of different options is similar to repeating that tennis move during a training. Practice asking yourself many different questions, and tackling these one by one – you will learn to think more quickly and broadly over time.

4. Think tiny and daily.

If you want to learn a new skill, consistent deliberate practice is important. Let me break that into the key parts here. Consistent practice would mean daily practice. For art, Melissa Dinwiddie advices 15 minutes of playing around in the sandbox every day. I would suggest at least 1 pomodoro a day to explore some ideas. And make it deliberate practice: deeply concentrated work in which you allow your ideas to flow.

5. Just start. Anywhere.

If you are thinking about a research question, and have listed a number of possible paths to try out to take you to the solution, you are already making some good progress. Now don’t start guessing which of these possible paths would be the best option, and which of these are not good options. Just pick one of the options, and start playing around with it. Stop second-guessing yourself – you don’t know until you’ve tried it anyway.

6. When in doubt, ask “What if…?”

I’ve mentioned it before, and I’ll say it again: asking questions leads to creativity. If you have trouble listing the possible paths you could try out to solve a problem, then ask yourself questions. Try to see if you can take your research question out of its comfort zone and turn it around in the sunlight to see all the spots you haven’t studied before. Identify the “shadows” in your methods – which assumptions do you take for granted? What if these assumptions are not valid?

7. Take the riskier path.

Of course here we mean that it’s OK to make a bold assumption and see where it takes you when you are fiddling with ideas. We don’t mean that you have to go and start doing to riskiest things in the lab… Try out a new method, or a method from a different field. Look up some references that have not been cited that much anymore recently – they might have gone lost in the mists of time because they were simply not interesting, or because later generations of researchers all went with the same set of assumptions, dismissing different thoughts from before.

8. Dismiss all gremlins.

Ah, gremlins! When you are in your creativity-pomodoro-moment, stop criticizing your own work. Set a deal with yourself: I will tell the gremlins to wait at the door until I come out of the sandbox – and then they can vent their ideas for 5 minutes. And then tell yourself: this opinion is brought to me by my gremlins, use with caution.

9. Spring the Comparison Trap.

Your process of training your creative muscle. Your research. Your sandbox. There’s no need to compare yourself and your progress to anyone else, so stop wasting time and energy doing so.

10. Treat yourself with compassion.

A truth truer than any of the truisms I’ve been throwing around! Be nice to yourself, don’t beat yourself up. If you go into your creativity pomodoro for the day, and nothing good comes out of it, then so be it. Again, the goal of the exercise is not to produce results, but simply to train your creative muscle. If something interesting comes out of it, so much the better. If not, that’s perfectly fine.

Have you tried out a creativity-pomodoro for a certain stretch of time? What are your experiences?